Faszinierender Blick in die Studienschach-Küche

von Walter Eigenmann

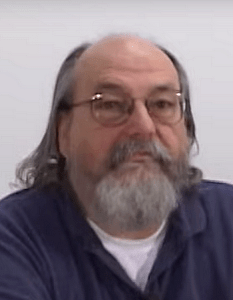

Der 72-jährige Kölner Schachkomponist, -historiker, -feuilletonist und -schiedsrichter Gerhard Josten ist in der internationalen Schachszene seit Jahren eine ebenso markante wie produktive Persönlichkeit. Seinen Arbeiten, Büchern, Reportagen und Untersuchungen rund ums vielseitig schillernde Thema „Schach“ begegnet man in Schachzeitungen wie der Rochade Europa, auf Problemschach-Portalen wie der Schwalbe und bei anderen internationalen Turnier-Ausrichtern, in zahlreichen Monographien, ja sogar in einem gestandenen Schach-Roman. Sein neuester Coup: Die Studien-Sammlung „A Study Apiece“.

68 Studien-Komponisten aus aller Welt

Der umtriebige Enthusiast des Königlichen Spiels hat die Welt des Problemschachs um eine weitere Publikation bereichert, indem er 68(!) bekannte (und auch weniger bekannte) Autoren aus aller Welt einlud, je eine eigene Lieblingsstudie und deren Entstehungsgeschichte zu einer grossangelegten Anthologie beizusteuern. Das Resultat ist ein 280-seitiges Kompendium namens „A Study Apiece“ („Eine Studie pro Kopf“), das nicht nur international anerkannte Endspielschaffende und faszinierende Schach-Endspiel-Aufgaben versammelt, sondern auch sehr authentische Einblicke eröffnet in die kreative, teils auch skurile, immer aber faszinierende Werkstatt moderner Studienschöpfer.

Der umtriebige Enthusiast des Königlichen Spiels hat die Welt des Problemschachs um eine weitere Publikation bereichert, indem er 68(!) bekannte (und auch weniger bekannte) Autoren aus aller Welt einlud, je eine eigene Lieblingsstudie und deren Entstehungsgeschichte zu einer grossangelegten Anthologie beizusteuern. Das Resultat ist ein 280-seitiges Kompendium namens „A Study Apiece“ („Eine Studie pro Kopf“), das nicht nur international anerkannte Endspielschaffende und faszinierende Schach-Endspiel-Aufgaben versammelt, sondern auch sehr authentische Einblicke eröffnet in die kreative, teils auch skurile, immer aber faszinierende Werkstatt moderner Studienschöpfer.

Die Teilnehmer-Liste von Jostens umfangreicher Sammlung – das Vorwort schrieb übrigens kein geringerer als der EG-Gründer John Roycroft – liest sich dabei wie das „Who-is-who“ der aktuellen internationalen Schachstudien-Szene: Lebende Legenden wie John Nunn und Pal Benkö oder Problemschach-Prominente wie Michal Hlinka, Mikhail Zinar und Jan Rusinek steuerten ihr ganz persönliches „Best-of“ ebenso bei wie solche unbekannten, aber innovativen Komponisten wie Ilham Aliev, Marco Campioli, Yuri Roslov, Gheorghe Telbis oder Wouter Mees – der interessanten Köpfe wären noch einige. Natürlich kann man in solchen Anthologien immer auch ein paar wichtige Namen vermissen; so hätten meines Erachtens Kostproben verschiedener jüngerer, aber nichtsdestoweniger einflussreicher Autoren wie beispielsweise Abdelaziz Onkoud, Piotr Murdzia oder Miodrag MladenoviÄ den Band noch zusätzlich aufgewertet.

Simple, aber ästhetisch ansprechende Studien

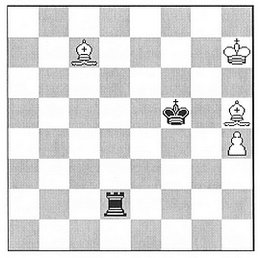

Und wenn wir schon bei den Schönheitsfehlern sind: Schade, dass den jeweiligen Hauptdiagrammen nicht die gleiche grafische Sorgfalt zuteil wurde, wie sie ansonsten den Band auszeichnet; solche grobpixeligen Illustrationen – wohl durch Vergrösserung entstanden – dürften eigentlich nicht mehr vorkommen im Zeitalter hochtechnisierten Desktop-Publishings, erst recht nicht bei einem stattlichen Buchpreis von knapp 30 Euro. Ansonsten ist „A Study Apiece“ aber ein layouterisch zwar einfach, aber durchaus ansprechend gestalteter, auch buchbinderisch solide gefertiger Band mit zahlreichen Diagrammen, Fotos und viel Varianten- wie Fliesstext; alles in allem sein Geld sicher wert.

Die von den 68 Buchautoren präsentierten Aufgaben kommen so vielfältig-heterogen daher wie die Biographien ihrer Schöpfer bzw. die Geschichte(n) ihrer Entstehung. Neben simplen Sechsteinern, die im Zeitalter der Datenbanken keinerlei endspieltechnische, wohl aber ungebrochen ästhetisch-künstlerische Bedeutung haben (wie obenstehendes Beispiel von J.M. Loustau zeigt), stehen hochkomplexe Patt-Konstrukte wie z.B. Per Olins Stück (rechts), und natürlich sind innerhalb der beiden Grundforderungen, die eine richtige Endspiel-Schachstudie immer stellt – nämlich entweder a) „Weiss zieht und gewinnt“ oder b) „Weiss zieht und hält remis“ -, zahlreiche „klassischen“ Motive der Studien-Geschichte und deren gewachsene „Studienschulen“ anzutreffen.

Studien-Komposition im Computer-Zeitalter

Wie stehen eigentlich die heutigen Studien-Komponisten zum Problemfeld „Computer“? Charakteristisch hierzu scheint das Statement des bedeutenden neuseeländischen Autors Emil Melnichenko zu sein, der (S.153ff) schreibt: „Today, I usually check my work with a computer, but I never totally trust the machine, and I certainly never use it to garner ideas, because I do not know how, nor do I enjoy the human computer interface, in fact, I find it tedious, distracting and contra the artistic spirit that employs serendipity as muse.“ Und weiter stellt Melnichenko klar, dass er zwar um die Präzision der sog. EGTBs wisse, aber trotzdem an der Jahrhunderte alten Konvention festhalte: „Computer literate composers are welcome to make use of their power but as a dinosaur I still remain attached to the primitive and manual method of composing that employs a tangible medium I have enjoyed since youth, in preference to one I personally find self defeating.“

Schachprogramme entlarven preisgekrönte Aufgaben

Natürlich ist ein solches Selbstverständnis des „artistic spirit“ zu respektieren, gleichwohl muss leise angemerkt werden, dass in den einschlägigen Studien-Datenbanken mit ihren abertausenden von Aufgaben zahlreiche – teils bekannte, ja als „historisch wertvoll“ deklarierte – Stücke lagern, deren Lösungszüge das doppelt vergebene Ausrufezeichen keineswegs verdienen, sondern vielmehr von dem ach so tumben Computer unbarmherzig als nebenlösige oder gar inkorrekte Kompositionen entlarvt werden. Heutzutage tut ein Studien-Autor also gut daran, seine Vielzüger- bzw. -steiner dem finalen Röntgenlabor seines heimischen Silikanten und dann erst dem internationalen Schiedsrichter zuzustellen… (Inwieweit auch „A Study Apiece“ fehlerhafte Aufgaben enthält, habe ich nicht en détail untersucht; anzunehmen ist aber, dass Herausgeber (und Computerschach-Sympathisant) Josten diesbezüglich seine Hausaufgaben gemacht hat).

Nichtsdestoweniger soll in diesem Zusammenhang eine warnende Stellungnahme des bulgarischen Schiedsrichters Petko Petkov nicht unterschlagen werden (S.14ff): „Because at present we have many bad examples with using of ‚Nalimov’s databases‘ I think that this threat to endgame genre is very serious an can be fatal in near future when this databases can embrace settings with 7 pieces on the board. But after that can follow also envelop of 8,9 etc. positions. If the Nalimov’s tables give all positions with 7 pieces […] the ‚moving-formula‘ for the many endgames can be: x+7 where all new themes and ideas the composer should demonstrate only in this ‚introduction‘ with ‚x‘ pieces, because after it all is without any sense banal known. As professional lawyer I should say that at present very important for the world endgame – composition ist the question for the copyrights in the light of existence of Nalimov’s databases. If after x moves we receive a position with 6 pieces which is computer – Nalimov’s position the main question ist obviously how fare are original these x moves as an introduction…“

Von der kurzen Notiz bis zur mehrseitigen Analyse

Die je spezifische Art, wie die 68 Co-Autoren des Bandes ihre Werke vorstellen, wirft ein bezeichnendes Licht auf ihre Komponisten-Persönlichkeit: Einigen wie z.B. Javier Ibran genügen zwei Seiten, zwei Diagramme, zwei Varianten und ein paar Sätze, um ihre Lieblingsposition in Szene zu setzen, andere wie z.B. Siegfried Hornecker erläutern ihren kompositorischen Höhenflug auf fünf und mehr Seiten mittels ausgiebiger Verbalität, wieder andere (z.B. Daniel Keith) stürzen sich variantenverliebt in geradezu Hübnersche Abspiel-Orgien.

Dieser immer sehr subjektive, für den Leser interessant und authentisch wirkende Zugriff aller Komponisten auf ihre ganz persönliche „Top-One“-Stellung ist die grosse Stärke von „A Study Apiece“. Gerhard Josten legt mit dieser Endgame-Anthologie keine erschlagende Fülle von hunderten Aufgaben vor, sondern ein fast intimes, autobiographisches Kaleidoskop der Herstellungsverfahren und der individuellen Motivation der Studien-Schaffenden. In dieser betont persönlich-offenen Art des Einblicks in die internationale Werkstatt der Endspiel-Komposition sucht dieses Schachbuch von Herausgeber Gerhard Josten seinesgleichen. (Selbstverständlich ist der Band bei solch internationaler Autorenschaft komplett in englischer Sprache gehalten). Eine sehr willkommene, die bestehende Problem-Bibliothek bereichernde Buch-Edition. ♦

Gerhard Josten (Hg.), A Study Apiece (68 Studien-Autoren und ihre Lieblingsaufgaben – engl.), Edition Jung Homburg, 280 Seiten, ISBN 978-3-933648-38-9

Lesen Sie im Glarean Magazin zum Thema „Problemschach und Schachstudien“ auch über András Mészáros: 1000 Schach-Endspiel-Studien

English Translation

(Thanks to John Rice/UK)

A fascinating look into the world of the chess study

72-year-old Gerhard Josten, from Cologne, is a chess composer, historian, feature-writer and judge. For many years he has been both a notable and at the same time a productive figure on the international chess scene. His work, his books, reports and investigations concerning the multifaceted and enigmatic subject that is „chess“ can be found in chess magazines such as Rochade Europa, in chess-problem outlets like Die Schwalbe and at other international tourney events, in numerous monographs and even in a mature chess novel.

Now this energetic enthusiast of the royal game has enriched the world of chess composition with another publication. He invited each of 68 (!) well-known (and less well-known) composers from all over the world to contribute one favourite study from their own output, along with details of its genesis, to be included in a wide-ranging anthology. The result is a 280-page volume entitled „A Study Apiece“ which, with its assembly of internationally recognised names, provides not only a collection of absorbing chess endgame-studies but also a genuine insight into the creative and sometimes comical yet always fascinating workshop of present-day study-composers.

The list of contributors to Josten’s extensive collection, with its preface written by no less a figure than EG-founder John Roycroft, reads like a „Who’s who“ of the current international chess-study scene. Living legends such as John Nunn and Pal Benkö or leading figures of compositional chess like Michal Hlinka, Mikhail Zinar and Jan Rusinek sent in their very personal „best“ selections, alongside lesser known yet innovative composers such as Ilham Aliev, Marco Campioli, Yuri Roslov, Gheorghe Telbis or Wouter Mees and a number of other interesting figures. Of course it’s always possible with such anthologies to regret the absence of important names; in my view the inclusion of samples from various younger but no less influential composers such as Abdelaziz Onkoud, Piotr Murdzia or Miodrag Mladenovic, to name just a few, would have appreciably enhanced the value of the work.

And while we’re on the subject of shortcomings, it’s a pity that the main diagrams were not accorded the graphical care that characterises the rest of the book. Such unrefined illustrations, doubtless enlargements, have no place in the digital age of desktop publishing, especially not in a book with a cover price as high as 30 Euros. But otherwise „A Study Apiece“, with its admittedly simple layout, is attractively produced in a robust binding, with numerous diagrams and photos, and text typeset both for variation-play and for continuous reading. All in all it’s certainly worth the asking price.

The studies of the 68 contributors appear just as varied as the biographies of their composers and the details of the works‘ genesis. Alongside simple 6-piece items, which in these days of endgame databases have no technical significance but still display a certain aesthetic artistry (like Loustau’s diagrammed example), one finds highly complex stalemate constructions such as Per Olin’s study (diagrammed). And of course within the two basic stipulations found in all genuine chess endgame studies, viz. (a) White to play and win or (b) White to play and draw, one comes across innumerable „classical“ features from the history of studies and the various study-schools that have arisen.

What is the attitude of today’s study-composers to the thorny question of computers? This statement (p.153ff) from the eminent composer from New Zealand, Emil Melnichenko, seems typical: „Today, I usually check my work with a computer, but I never totally trust the machine, and I certainly never use it to garner ideas, because I do not know how, nor do I enjoy the human computer interface, in fact, I find it tedious, distracting and contra the artistic spirit that employs serendipity as muse.“ And Melnichenko goes on to affirm that while he knows about the precision of so-called EGTBs he still sticks to the centuries-old convention: „Computer-literate composers are welcome to make use of their power but as a dinosaur I still remain attached to the primitive and manual method of composing that employs a tangible medium I have enjoyed since youth, in preference to one I personally find self-defeating.“

Naturally this awareness of the „artistic spirit“ commands respect. At the same time it must be observed that in the relevant study databases with their many thousands of compositions there are numerous items stored, in some cases well-known and in others deemed to be „of historical value“, whose solutions contain moves that in no way merit the double exclamation-mark but which are mercilessly revealed by the crass computer to be cooked or completely insoluble. Nowadays a composer is well advised to give his study, if it has many moves and/or pieces, to the x-ray lab of his personal silicon-friend before submitting it to the international judge… (I have not investigated in detail whether „A Study Apiece“ contains faulty compositions; but it is to be assumed that editor Josten, who is by no means averse to computer-chess, has done his homework in this regard.)

Nevertheless a note of caution is sounded in this connection by Bulgarian judge Petko Petkov (p.14ff), and it deserves a mention: „Because at present we have many bad examples with using of ‚Nalimov’s databases‘ I think this threat to endgame genre is very serious and can be fatal in near future when this databases can embrace settings with 7 pieces on the board. But after that can follow envelop of 8, 9 etc. positions. If the Nalimov’s tables give all positions with 7 pieces […] the ‚moving-formula‘ for the many endgames can be: x+7, where all new themes and ideas the composer should demonstrate only in this ‚introduction‘ with ‚x‘ pieces, because after it all is without any sense banal known. As professional lawyer I should say that at present very important for the world endgame-composition is the question for the copyrights in the light of existence of Nalimov’s databases. If after x moves we receive a position with 6 pieces which is computer-Nalimov’s position, the main question is obviously how fare are original these ‚x‘ moves as an introduction…“

The individual manner in which the 68 co-authors of the book present their work casts a distinctive light on their composing personality. Some, like e.g. Javier Ibran, need no more than 2 pages, 2 diagrams, 2 variations and a few sentences to tell us everything about their chosen position. Others, e.g. Siegfried Hornecker, spread themselves over 5 or more pages of elaborate verbosity, while others again (e.g. Daniel Keith) take delight in plunging into an orgy of variations in a manner worthy of Hübner.

The way each composer approaches his personal favourite position is always very subjective and interesting to the reader, and it conveys a truly genuine impression. This is the great strength of „A Study Apiece“. In this endgame anthology Gerhard Josten does not offer a deadening mass of hundreds of studies, but an almost intimate, autobiographical kaleidoscope of study-composers‘ processes of creation and individual motivation. This work by editor Gerhard Josten provides an emphatically personal insight into the international workshop of endgame composition, and as such it is unlike any other chess book. (Of course with contributions on an international scale the book is in English throughout.) A very welcome publication that enriches the existing library of chess composition. (Walter Eigenmann) ♦

Lesen Sie im Glarean Magazin zum Thema Schach-Studien auch von Mihai Neghina: Dame im Käfig